Advertisement

Advertisement

Credit Impulse Flashes a Warning to Major Economies

Published: May 23, 2019, 12:18 GMT+00:00

Cracks are spreading across markets' cheery Q1 facade, and it doesn't all come down to trade war headline risks. A key leading indicator is falling again, and Saxo Head of macro Analysis Christopher Dembik fears this might only be the beginning.

At the start of the year, the consensus narrative was that growth was well-oriented and risks were limited despite the threat of trade war and sluggish global trade overall. Many analysts still consider growth to be solid, citing solid Q1 GDP growth in several key major economies. Looking at the US and Japan, however, growth is not as resilient as it seems. In both countries, the strong Q1 figures were mainly driven by an increase in stockpiling, which is not the sign of an incredibly dynamic economy.

There is more bad news, as well: it may get worse. We make this bold statement based on the recent fall in credit impulse. Economists used to refer to the stock of credit to understand the business cycle, but academic research since the great financial crisis (Biggs, Calvo, Ermisoglu) pointed out that the flow of new credit – what we call credit impulse – is a better method of assessing where the economy is heading. Credit impulse leads the real economy by nine to 12 months with a correlation of 60%.

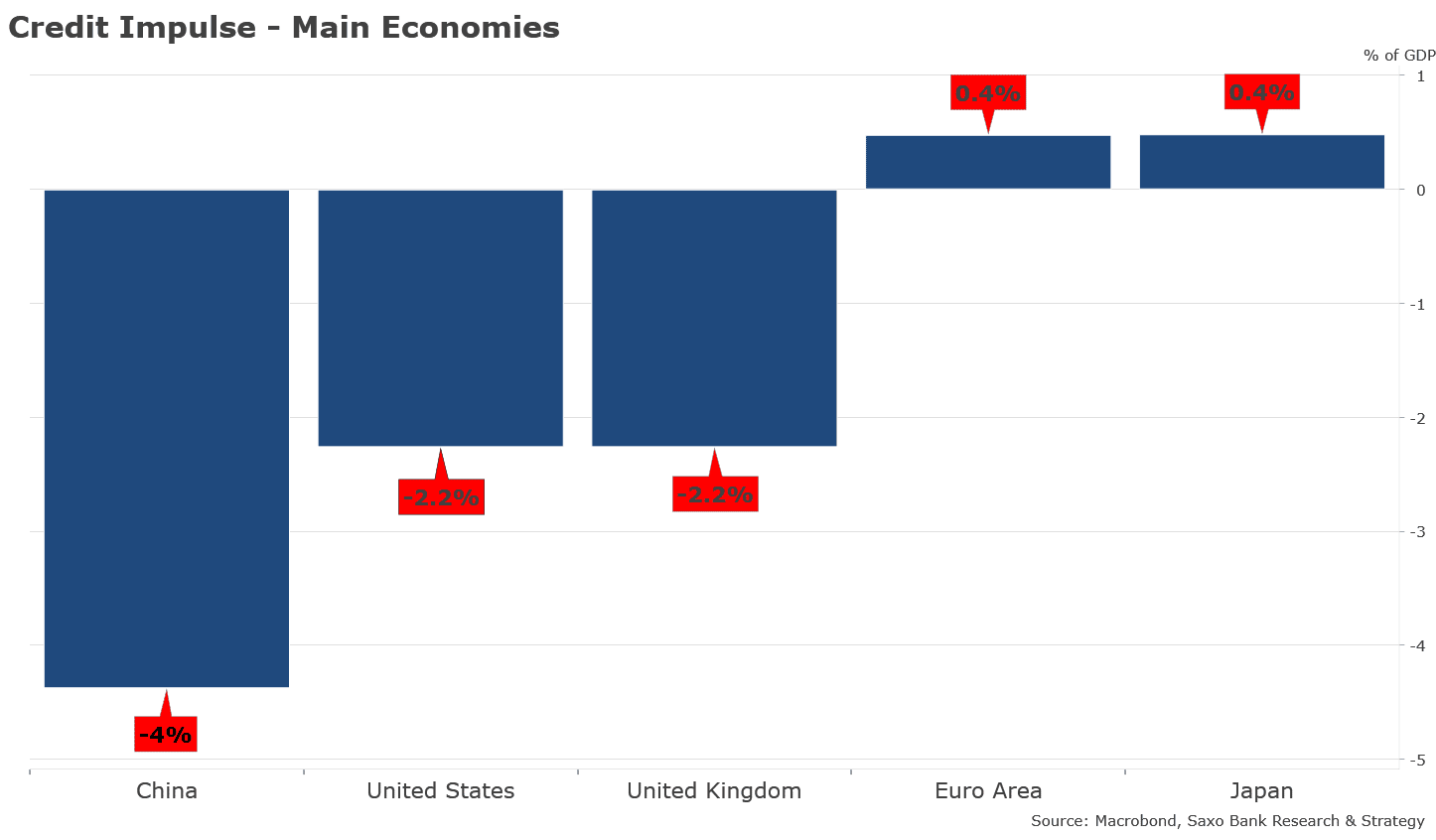

Based on our latest estimates, global credit impulse is falling again and now stands at -1.8% of global GDP. The amplitude of the contraction is similar to that seen in Q4 ‘15. That year, the decrease in credit impulse led to the lowest global growth level seen in the current cycle, with global GDP growth reaching just 3.09% in 2016. We have not yet reached that point, but recent developments on the trade war front urge caution on growth forecasts.

So far, half of the countries in our sample are in contraction and the other half, excepting certain emerging market countries like India and Russia, are experiencing a deceleration in the flow of new credit in the economy. In developed countries, the trend is most concerning in the US. US credit impulse is running at -2.2% of GDP, the lowest level since 2009.

The US Composite Leading Indicator, watched by asset managers all around the world, is also confirming this negative signal with the index now at its lowest point since Autumn 2009; the year-on-year rate has fallen from 0.68% to -1.65% over the past 12 months. Such levels are usually consistent with the risk of recession. In addition, the three-month moving average of the Chicago Fed National Activity Index, which gives a broad overview of the state of the economy, is back to where it was in Spring 2016.

With the US economy no longer supported by massive tax cuts and facing the negative economic consequences of the trade war, particularly those felt by US consumers, the outlook may continue to deteriorate in the months to come. This reinforces our call that the current business cycle, especially in the US, is more fragile than most suspect.

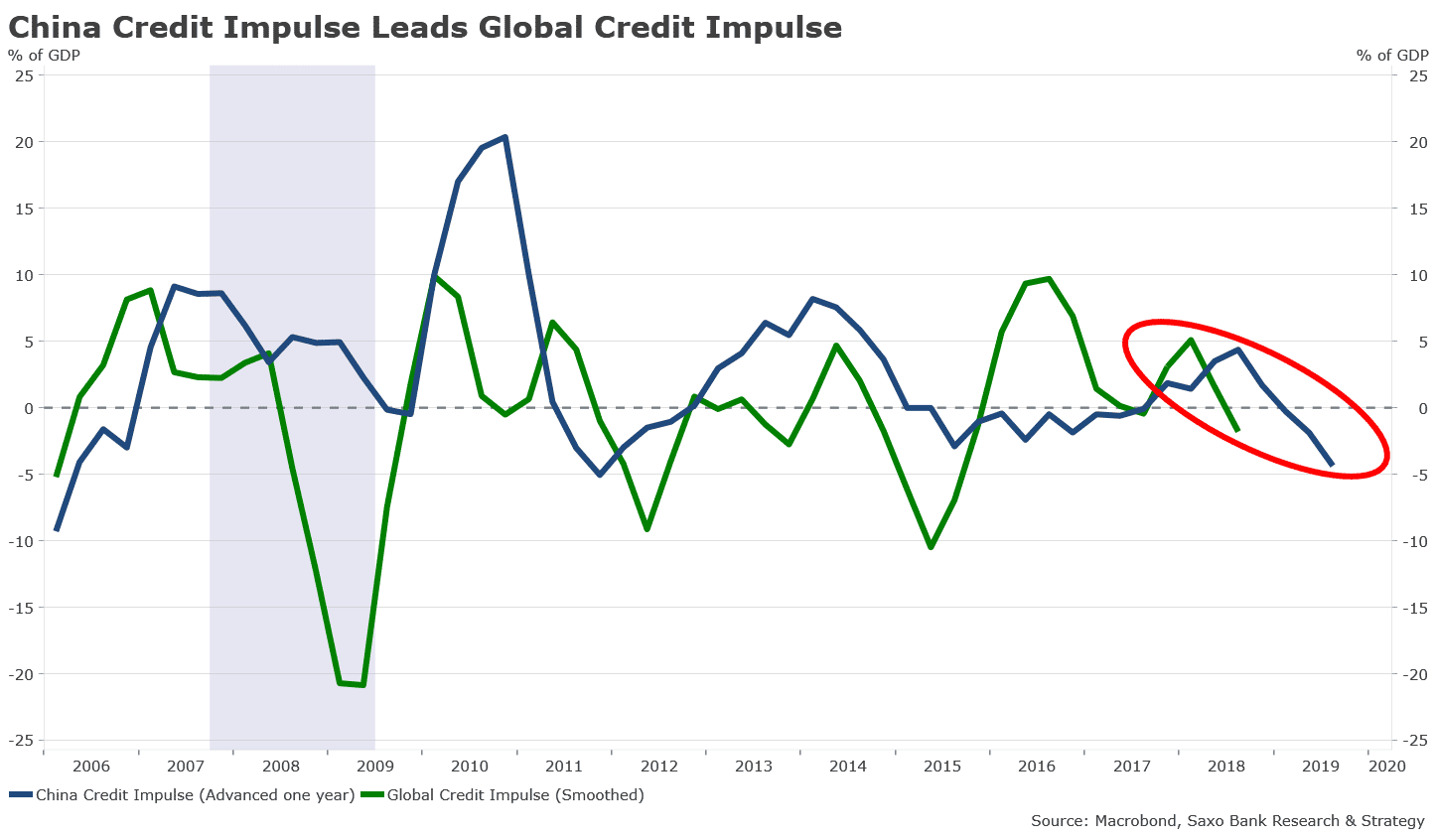

We fear this is only the beginning. As you can see in the chart below, we have plotted the global credit impulse against the Chinese credit impulse. China’s credit impulse, which roughly represents 1/3 of the global growth pulse, tends to lead the global credit impulse by one year. As long as the Chinese credit impulse does not return to positive territory, we expect the global credit impulse to move downward in the coming quarters leading to lower-than-expected growth.

The policy response will be crucial in the near term. Due to trade war-related uncertainty, investor belief in a global V-shaped recovery in H2 is growing less certain. We think China is ready and able to further open its credit tap to mitigate the impact of trade war, but this is a challenging task that implies the implementation of very targeted support policy. The goal here would be to avoid fueling the debt bubble as much as is possible. The manufacturing goods sector, most notably the communications sub-sector, represents the largest share of Chinese exports and thus is the most vulnerable to ongoing tensions. It will certainly be subject to support measures very soon.

There is little doubt that China can stimulate its economy, but the same is less certain for the US and the euro area due to policy constraints. In the US, fiscal policy has already been deployed, ultimately fueling a massive federal deficit in a period of growth. The tax cuts had a very strong macroeconomic impact, but the effect could be completely erased if the Trump administration decides to impose a 25% tax on the remaining share of Chinese imports worth $300 billion. Investors expect a lot from the Federal Reserve – bets of a rate cut at December Federal Open Market Committee meeting stand around 60-70%, although it remains quite early to call such a move.

This is also simply not the way that policymaking works at the Fed. We have all noticed the red signals related to the trade war but based on the Fed’s track record, this is not sufficient for a rate cut. At best, we can only really expect a dovish adjustment of forward guidance at this point. For a rate cut to manifest, we would need a combination of lower inflation, a sharp decrease in consumption and tighter financial conditions, and this is not yet the case. The risk is therefore high that investors will be disappointed by the Fed’s answer to rising trade tensions.

My final word comment concerns the euro area. Potential growth here is lower than in the US, which explains why growth is not higher. Despite headwinds hitting the manufacturing sector, domestic demand is resilient. There is little margin for the European Central Bank to stimulate the economy in case of a pronounced downturn (a new round of TLTRO is clearly not enough) so the only leverage left is fiscal policy, but we have very strong doubts that EU policymakers will be able to reach a common ground on that topic.

Populist parties, particularly in Italy, are pushing for further fiscal stimulus. This could make sense if we are talking about coordinated productive investments, but they are constrained by the Stability and Growth Pact that should, but probably never will, be reformed. In other words, despite being the second global economic power, the EU is still one of the weakest points among developed markets due to its lack of any real policy response capacity.

Christopher Dembik, Head of Macro Analysis at Saxo Bank.

This article is provided by Saxo Capital Markets (Australia) Pty. Ltd, part of Saxo Bank Group through RSS feeds on FX Empire.

About the Author

Christopher Dembikcontributor

Christopher Dembik joined Saxo Bank in 2014 and has been the Head of Macro Analysis since 2016.

Advertisement